“Wishing you a very happy holiday and a great New Year 2019. Cheers Bernie.”

Upon receiving Season’s Greetings from Bernard Marks we had little inkling that these would be the last words we would share. Just a few days later, on December 28 2018, Bernard died. Together we had just forged plans for his next visit to the Max Mannheimer Study Center. News of his sudden passing shocked us all the more.

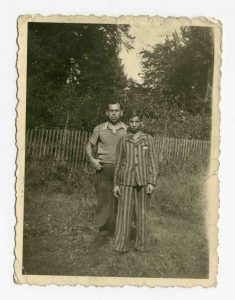

Bernard Marks in his prisoners‘ clothing with his father Joseph shortly after the liberation

For the last ten years Bernard Marks had been a regular guest at the Max Mannheimer Study Center and reached out to over 600 youths in his moving contemporary witness talks, giving a vivid account of his persecution at the hands of the Nazis. Born in 1932 as Ber Makowski into a middle-class merchant family in Łódź, following the German occupation of Poland the family was forced to move into the Łódź ghetto (Litzmannstadt) in 1940. His wealth of personal memories of this time mirrored the harsh everyday life in the ghetto from a child’s perspective. After the ghetto was disbanded, the family was deported to Auschwitz in 1944, where his mother Laja and younger brother Abraham were murdered immediately upon arrival. “My father, my angel” was something he often said, referring to how his father Josef Makowski forward dated the birthday of his son Ber by five years, thus saving him from imminent death. He was now considered old enough to work and together with his father he was deported from Auschwitz to Kaufering, where in the Dachau subcamp complex he was forced to work for the German armaments industry under cruel and appalling conditions. After spending five years of his childhood in captivity, he – aged just 13 – was liberated by American troops on April 27 1945. Until his emigration in 1947, Bernard Marks – who changed his name once he arrived in the U.S. – attended various schools in Landsberg, Feldafing and Freimann, as well as spending some time in the DP children’s center run by the UNRRA at Prien on Chiemsee. In his presentations, which he augmented with striking photo and video material, he not only gave an account of historical events but also reflected on the difficulties in dealing with the past, warned against the dangers of forgetting, and motivated the younger generation to take a stand against racism, antisemitism, and xenophobia while doing what they can to foster peaceful and tolerant cooperation with one another.

Bernard Marks in front of his photographic portrait in the Max Mannheimer House

In the U.S. Bernard Marks studied engineering and worked for many years in the aeronautics industry before setting up business as a consultant on sustainable energy. He continued to advise companies and universities worldwide and offer his expertise until an advanced age. Bernard Marks remained extremely active to the end politically as well, bravely expressing his views on social and political developments in his home state of California. He was particularly concerned about the situation of minorities, with his own personal story of persecution creating a bond with their plight. Shocked at the rigid implementation of American immigration policy, at a forum he candidly told representatives of police and customs enforcement agencies, including the then director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “history is not on your side!” This forthright statement caught the attention of many on the internet, where he then became a prominent figure, his contribution to the debate shared extensively on social media and picked up by the international press.

Teamexcursion to Kaufering with Bernard Marks

Bernard Marks was a sociable and big-hearted person who was open to others and always approachable. He found some level of interaction and communication with almost everyone he met. His family was always close to his heart and he cultivated many friendships around the world. In Sacramento he was a highly-respected member of the Jewish congregation of B’nai Israel, participating in the life of the community for decades and singing in the choir right up until his death.

In 2008 Bernard Marks initiated in memory of his deceased wife the “Eleanor J. Marks Holocaust Project”, an essay competition for students worldwide that invites them to write a piece on different topics concerned with the Nazi persecution of the Jews. He coordinated the competition personally and did all that he could – investing both much time and money – to ensure that the project was a success.

Bernard Marks with Nina Ritz 2016

For the staff at the Max Mannheimer Study Center, “Bernie” was not only a valued supporter of our work but also a good friend. During his visits to Dachau we also spent much leisure time with him. Open-minded and outgoing, he was ready for any undertaking: an evening meal celebrating the Shabbat, excursions into the countryside with coffee and apple strudel, visits to museums and theme parks. With a wide range of interests, full of energy, unafraid to speak his mind and possessing a good sense of humor, Bernie Marks was a wonderful companion – his passing is a huge loss and he will be very sorely missed.